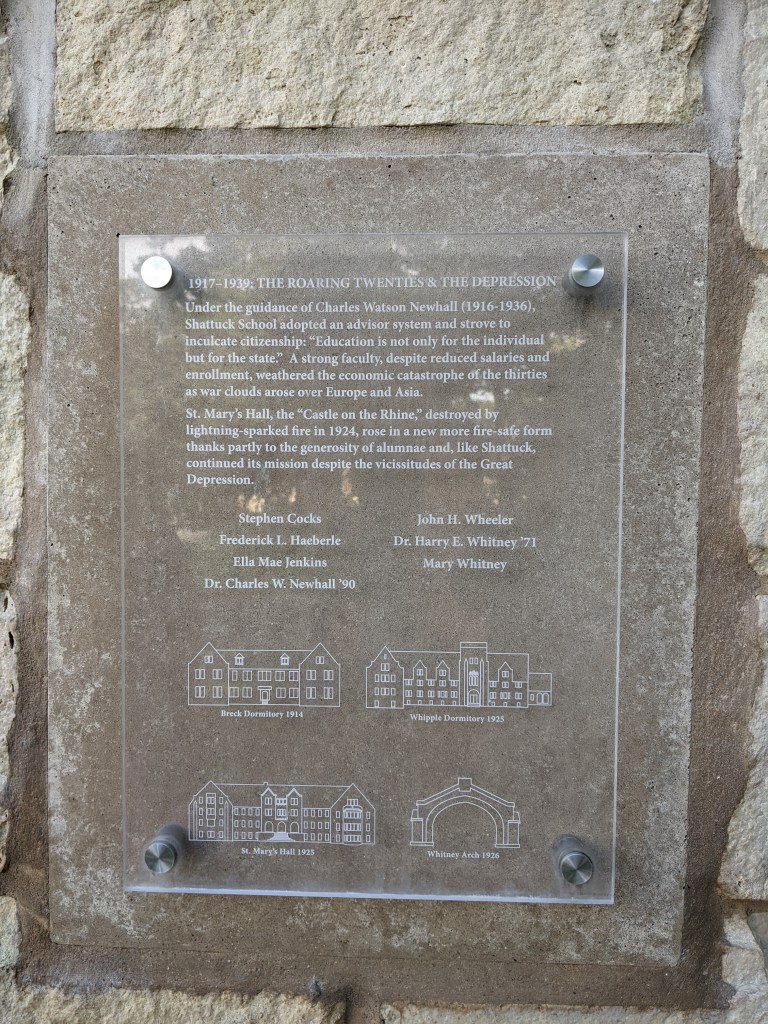

After I drove through the old limestone arch, Google Maps took me the wrong way around the parade grounds of Shattuck-St. Mary’s School. Retired librarian Richard Kettering was waiting for me outside the clock tower of Shumway Hall, which dates from 1887. Richard kindly introduced me to what Kiyoshi Kitagawa’s world might have been like when he was on campus between 1927 and 1932. When Kiyoshi arrived at Shattuck School, the dorm Whipple Hall was brand-new. Suits of armor no longer guard the entrance, but gargoyles still scowl from opposite sides of the heavy exterior door. Richard showed me a small vacated dormitory room used by ordinary cadets. Aside from the radiator, little remains that speaks of the late 1920s and early 1930s. A single window opened northward to a wooded area, far beyond which lay Minneapolis. I wondered if Kiyoshi gazed out a similar window, thinking of home. South of Whipple Hall and the cluster of upper school campus buildings, assorted trees create calm by the Chapel of the Good Shepherd. This tamarack tree was there in Kiyoshi’s time, said Richard. Long ago one headmaster mistakenly concluded the tree was dead when it shed its golden needles and ordered it to be cut down, but a biology teacher intervened to save the tree.

At the outset Shattuck had both Native American and white children, but by the time Kiyoshi attended there seems to have been no Native American boys. If there had been, they may have watched the tamarack turn color every year, knowing that their families were catching whitefish back home. At one time tamaracks were the most common tree in Minnesota. The man who built the campus is said to have been an Anglophile. He hired the same architect who built Carleton and St. Olaf in next-door Northfield to build a Gothic-inspired campus. Perhaps he planted the tamarack thinking about its English larch tree relatives. According to the Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland, a man named James Murray, the second Duke of Atholl (1690–1764), started “modern plantation forestry” in Britain by planting thousands of hectares of larch, both native and Japanese.

Ever since I first read about Kiyoshi being sent to this Christian military boarding school in rural Minnesota, I worried about him as if he were my child, even though he was born in 1914 and would have been a few years younger than my grandparents. Kiyoshi’s family visited him on Sundays, visiting day at Shattuck, driving two hours each way. The visits dropped off when the store got busy. Over lunch with his parents at the Blue Bird Inn, perhaps Kiyoshi revealed what really happened in this scene from the school newspaper gossip column.

The Shattuck Spectator, “Diary of a New Yap,” Wednesday, February 27, 1929.

Tuesday, February the Nineteenth.

. . . Kitagawa, it is alleged, breaks Clements pickle eating record by consuming 43 at a sitting. In accomplishing this feat he was assisted by Hornburg, manager, Lentz, J, sparing [sic] partner, Hastings, referee, and Morris, water boy. Young was the official witness. It really seems as though we had a new record. It is the more remarkable in that Kitagawa drank five (5) glasses of water and ate two cream puffs at the same meal and yet was able to leave the dining room under his own steam.

Sunlight streamed through south-facing stained glass windows framed in dignified arches and reflected off of the whitewashed plaster walls. From the dark wood-paneled ceiling, chandeliers hung in rosettes of five or more lamps. Sconces lit the sides of the windows and doorways. Long tables covered in white tablecloths stood in military-crisp rows. High on the walls, portraits of distinguished men peered from ornate frames in varying sizes. Perhaps the dining room was nearly empty, the upperclassman in the hash pulpit having assumed their leadership duties throughout campus. At one table, five white boys crowded around a small fourteen-year-old Japanese boy. Kiyoshi was in his second year at Shattuck, equivalent to his high school freshman year. Hornburg and Lentz were sophomores, and Morris and Young were juniors. The fifth boy Hastings did not appear in the yearbook directory that year, so his age and hometown remain unknown. Of the five boys, only Lentz was in Kiyoshi’s Company C. Hornburg, Young, and Morris were from Company B, and Hastings from Company D.

If we could interview Kiyoshi or the others present, their recollections would probably contain elements of these two options.

- We take this account at face value. Teenagers can eat a lot. Furthermore, until the fall of 1927 Kiyoshi lived with his Japanese family. Although Japanese ingredients were scarce in Minneapolis back then, he might have enjoyed pickles and rice occasionally. Perhaps he wished to impress upon his Shattuck peers that Japanese have a high tolerance for sour food. Or that some small bodies come with big stomachs. (Seventy-two years later, a slim young Japanese man Takeru Kobayashi demonstrated this to the world by winning Nathan’s Hot Dog Eating Contest on Coney Island, New York.)

- This account might describe a hazing incident coded to elicit giggles from cadets in the know. The March 6, 1929 gossip column referred to a newly formed Gawa Pickle Corporation and an attempt to break Kiyoshi’s record. If this is the case, the context suggests a tacitly accepted initiation ritual. That year Lentz’s older brother served as the Spectator editor-in-chief and rose to other leadership positions. Lentz himself, named as a “sparring partner,” was also on the staff. It seems unlikely that two brothers on the newspaper staff would publicize an incident that would incriminate one of them.

That year, Kiyoshi appeared in the gossip column several times. The May 1, 1929 issue mentions Kiyoshi again with boys from the pickle story. “Hornberg tells Kitagawa about snipe hunting” suggests that Hornberg (the “manager”) may have sent Kiyoshi on a snipe hunt first and explained the joke later. “Kitagawa is not paying attention to Lentz J. ‘Can’t you hear me?’ ‘No!’ ” Both Kiyoshi and Lentz entered Shattuck the previous year in Company C. They would have drilled together. Like Kiyoshi, the Lentz brothers were from Minneapolis, albeit a few streetcar lines away. The playful tone of this column and the context from other columns hint that Kiyoshi and Lentz might have been friends. Since Lentz’s older brother was a school leader, Lentz’s friendship might have afforded Kiyoshi more social capital than he might have had otherwise. Furthermore, an issue from two academic years later, January 14, 1931, reported that Kiyoshi practiced hockey over winter break with Lentz and other Minneapolis Shads, as the cadets were called.

Richard Kettering started his tour by saying that Shattuck did not start out as a military school. Established as an Episcopal seminary, it became a grammar school, but after the Civil War the surplus of military people inspired the creation of military academies. Shattuck developed its religious and military cultures alongside the broader historical trend of muscular Christianity. In Kiyoshi’s day fellow cadets served as dorm heads, leading their charges to and away from Wednesday evening vespers services. The military curriculum was discontinued in the 1970s, when the Vietnam War made military service unpopular, but the Crack Squad, the precision rifle drill team that Kiyoshi tried to enter at least once, remained until 2019.

Shattuck-St. Mary’s now attracts students from outside the United States for its world-class sports programs. The faculty and staff help provide a home for their students, particularly the ones whose families live far away. Faculty members’ children played on the lawn as I drove into Shattuck-St. Mary’s for the first time, and later in the dining room as I had lunch with Richard and his colleagues.

We walked past the Johnson Armory, where the Crack Squad practiced and Shattuck held dances with its sister school St. Mary’s Hall. Large wooden plaques lining the halls displayed the names of notable Shattuck and St. Mary’s students. Football team captains. Students voted as the “most worthy boy.” Kiyoshi did not appear anywhere, but recent times list several Asian names. The stairway to the Hirst Library is too narrow for cadets to march up two abreast safely. Richard introduced me to the current librarian, who went out of her way to make me feel at home. In the library large rectangular windows facing south, west, and east let in late summer light and air. Cookies were set out on the table. A partly-completed puzzle invited students to manipulate pieces to form a picture illuminated by natural sunlight and overhead lamps rather than a blue screen. Couches and small seats arranged in circles welcomed reading, crafting, even a game of chess. A library photo in the January 21, 1931 Spectator shows wooden chairs and tables spread with periodicals. The hardwood floor would have announced every entrance and exit of cadets’ hard shoes. Although the Spectator reliably printed new library acquisitions, the photo shows no bookshelves.

From inside tightly framed black-and-white photographs on the bright plaster walls, military cadets watch students dressed in maroon-colored golf shirts and beige skirts or slacks. The current librarian showed me a painting between two south-facing windows. The original had hung there for years before it was appraised at an unexpectedly large sum. Rather than worry about keeping it in good condition, the school had a replica made and sold the original to fund a scholarship. Every frame held a story.

I carried the heavy bound copies of school newspapers to the reading tables. I photographed each spread and jotted notes on the columns where I was most likely to find Kiyoshi: the intramural sports pages and the gossip column. Although his yearbook caption asserted that he was “brilliant” in class, he rarely made the honor roll. The Spectator won awards in Kiyoshi’s day, but the reporting leaves unanswered questions for modern researchers. The Spectator listed Kiyoshi among cadets who took an advanced dancing class, but did not mention any beginner’s class. I filled spreadsheets with data on every page he appeared, and then consulted yearbooks to learn about the boys with whom he appeared in these columns. Where did they live? How likely were they to have been friends?

Kiyoshi might not have been the most popular guy with the top grades, but he had friends who appreciated his jokes. Perhaps this is one way he survived. He also survived by playing intramural sports in high-profile team sports: football, hockey, and baseball. In his first year, “speedy, flashy Kitagawa” and a much bigger boy distinguished themselves as the best new players for the Badgers, one of Shattuck’s two intramural teams. The following year the Spectator mentioned Kiyoshi in passing as a well-regarded batter.

While I was at the library, students, especially international students, walked in and chatted with the librarian. Even while she stepped away students congregated and spoke excitedly to one another in non-English languages. They made themselves at home. The Spectator provided hints of how the cadets made home long ago. Mrs. Woodruff’s cooking won rave reviews. The wife of the headmaster, Mrs. Newhall, hosted students’ parents when they came to visit. Even Mr. Kitagawa mentioned that she found Kiyoshi a young woman from St. Mary’s to take to the Junior-Senior Ball.

How did the world beyond Shattuck affect Kiyoshi’s experience? A few Shattuck students hailed from the West Coast, the home of congressmen who pushed for the ban on all Asian immigration in 1924. At the same time, alumni news articles indicate a globally connected student body. The December 10, 1930 Spectator noted that a 1913 alumnus managed the Brazilian branch of Firestone based in São Paulo. The same issue mentioned that an 1884 alum became the Vice President of Bank of Hawaii in Wailuku (Maui). Of course, the Spectator reported on only the most accomplished alums such as West Point and Ivy League students and university lecturers. But since these alumni remained in contact with Shattuck, they were likely to send their children there. Although many parents sent their wayward sons to Shattuck, the evidence also suggests a culture of prestige, privilege, and power.

This culture shaped any cosmopolitan tendencies on campus. In May 1930 Kiyoshi’s friend Lentz took a St. Mary’s student with a Swedish surname from the Philippines to the Junior-Senior Ball. Minneapolis newspapers mentioned that she had relatives in Minneapolis and otherwise treated her as another Minneapolis St. Mary’s student. Most students had some knowledge of Japan from newsreels, movies, and books. But most probably never had a Japanese American classmate before.

After Kiyoshi entered Shattuck, the world experienced further turmoil. The US stock market crashed in 1929, setting off a chain of events leading to the Great Depression. In 1931, Japan invaded China and annexed a portion that they called Manchuria, angering the US and other nations. Although the US wanted to preserve the status quo with China’s territory and government, it also wished to protect its own business and foreign policy interests. This incident illuminates the US–Japan imperial rivalry that had been brewing since the early twentieth century. In the meantime, some were working hard to maintain ties. In 1933 Kiyoshi’s father encouraged a Japanese import company to buy more Minneapolis flour and other American products. The following year Babe Ruth, America’s most popular baseball player, led a delegation of American baseball players through Hawaii, the Philippines, China, and Japan. Minneapolis newspapers duly reported on the friendly games.

In my previous blog post I mentioned that in 1933 the Daughters of the American Revolution recognized Kiyoshi as the best freshman ROTC cadet at the University of Minnesota. The three largest Minneapolis newspapers carried that story. The Minneapolis Tribune featured a front page photo and The Minneapolis Journal interviewed him. Since Kiyoshi was still a college freshman, this interview could shed light on how Shattuck shaped him. While some students opposed the mandatory military drills common in colleges and universities at the time, he supported them because the US needed a strong and expanded military. Kiyoshi valued his Shattuck military training and grew to link his own activity with the security of his nation.

This interview and other historical evidence reveal that more than eight years before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the US was preparing for war by holding military drills at non-military schools. At the time of Kiyoshi’s interview a group of students passed a resolution stating that they would not fight for the United States. Kiyoshi responded, “Their attitude is unpatriotic and it is indefensible. But I do not think the vote was representative of the University, at all. Those voting constitute the group of radicals on the campus.” After five years of military academy, Kiyoshi associated military service with patriotism, and he was prepared to set a positive example for his peers. Kiyoshi’s commitment to the US did start at his Japanese American home. His father’s diaries demonstrate a strong desire to raise his children as good Americans. At Shattuck these ideas grew stronger.

The reporter must have asked Kiyoshi his take on relations between Japan, China, and the US. “Kiyoshi has no definite opinions about the Japanese conflict with China, but was maintaining an ‘open mind’ upon the subject until he could be sure of the truth.” I try to imagine how Kiyoshi felt when he heard that question. How often had he been asked to speak about Japan, China, or any other country with people who resemble him? Did he develop responses like this to protect himself? On the other hand, “He laughed at the mention of the often repeated fear of a Japanese ‘threat’ to the United States.” The words “often repeated” slide quickly under the eye, but make me wonder if anyone at Shattuck, at the U, or in the streets of his hometown Minneapolis treated him as if he were a “Japanese ‘threat’ to the United States.” If so, he might have felt all the more pressure to appear indisputably American: “ ‘Japan would never be foolish enough to try to attack the United States,’ he said. ‘The distance is too far, this nation is too big—oh, there are many reasons. The whole idea is preposterous.’ ”

Although anti-Japanese sentiment was rising, The Minneapolis Journal gladly publicized Kiyoshi’s patriotism and commitment to serve in the military. The year after he graduated from the U, Kiyoshi left Minnesota. Except for a brief stint at the Military Intelligence Service Language School at Fort Snelling, he never returned to live.

What does it mean to us today that Kiyoshi attended Shattuck School between 1927 and 1932? Faribault linked to Minneapolis by local train and rural highways, but Shattuck and its sister school St. Mary’s lay within a network of American power that extended to and beyond the Pacific Ocean. Although Kiyoshi might appear to be an anomalous Japanese student at a predominantly white school, he too was part of a network that resulted from both American power extending into the Pacific and Japanese power extending toward the Americas. Japan’s participation in industrial fairs such as Chicago (1893) and St. Louis (1904) set the stage for Kiyoshi’s family to sell Japanese goods in Minneapolis and thereby afford private boarding school tuition.

I enjoyed spending the last day of class in May of this year talking to several history classes about Kiyoshi, his formative years at Shattuck, and how he contributed to the story of the US. Today, international students of all races make up about 23% of Shattuck-St. Mary’s student body. Perhaps Kiyoshi’s presence helped Shattuck think of itself as more cosmopolitan. Kiyoshi graduated Shattuck at the rank of first lieutenant, showing that his peers and the school leadership thought well of him even as antagonism toward Japan grew. The school newspaper and other evidence suggest that this short Japanese cadet survived and thrived at Shattuck by adopting a toughness consistent with the school culture: military discipline, performance in sports, and perhaps the ability to eat sour pickles. This tough culture at Shattuck also appeared on college campuses nationwide with both high-profile school sports and mandatory military drills. Today Americans celebrate the sacrifices of Kiyoshi and other members of the segregated Japanese American 442nd Regimental Combat Team. A closer look reveals how Kiyoshi’s story is also distinctively Minnesotan.

Many thanks to the Shattuck-St. Mary’s and Rice County Historical Society audience members who asked good questions and help me learn more about their community.

Wonderful post! And enjoyed reading this revealed history.

LikeLike